For all the money consumed in junior player development, why aren’t there tennis financial advisors? Has anyone taken the time to calculate the present value of future cash flows needed to develop an average national caliber junior from beginning to end? With so much uncertainty involved, probably not.

For all the money consumed in junior player development, why aren’t there tennis financial advisors? Has anyone taken the time to calculate the present value of future cash flows needed to develop an average national caliber junior from beginning to end? With so much uncertainty involved, probably not.

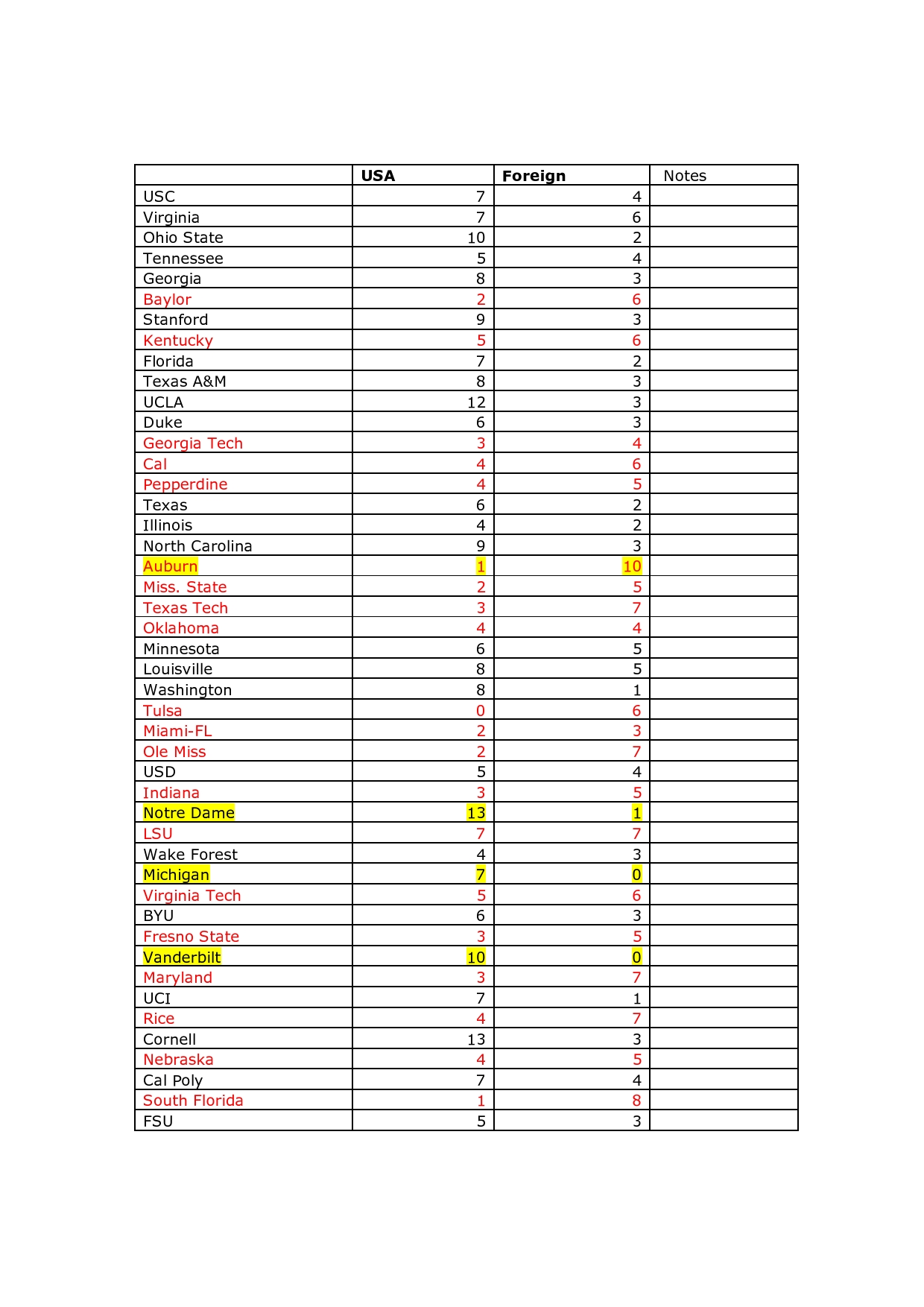

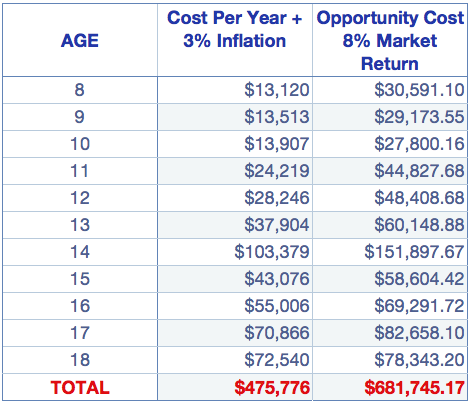

The available information is anecdotal at best. CAtennis.com comes to the rescue with a rough financial analysis of the costs associated with nurturing and maximizing talent from start to finish. Of course every family and child are unique and particular circumstances may differ (for example, living in Southern California and having access to outdoor facilities year-around versus the Midwest; playing at public courts v. having to join a private club; etc.). Therefore, a few assumptions are necessary before conducting the research:

- 8 year old boy with average tennis skills on a national level (this means that that player is no bigger or smaller than the rest of the kids and average in athleticism and other physical characteristics).

- Player comes from a upper middle-class family in the Los Angeles area (approximately $150,000 in combined income)

- Child and parent share a long-term intention of attending a top D1 tennis school (in other words, this is not just one of the many activities that the player will be involved in; this is the main, if not one and only, extra-curricular activity)

- Ultimate goal is to pursue a career in professional tennis

With these initial assumptions out of the way, it is time for some number crunching on a detailed annual basis starting with 2012. The proposed figures are purely hypothetical and should be analyzed through the lens of the picture painted above. The guestimation begins and all numbers are based on 2011 prices. Furthermore, this is a family that is totally committed to tennis (i.e., everyone is operating under the assumption that the child will pursue a serious tennis career which will include high-level college tennis and, perhaps, a shot at “the tour”).

2012 - Age 8

- Equipment - $400 (rackets, shoes, newest tennis clothes - gotta wear what Rafa/Roger wear, right?!)

- Group Lessons - $2,880 = 12 x $240 per month (3hrs x week @ $20 per group)

- Private Lessons - $2,640 = 12 x $220 per month ($55 per private)

- Membership Fees - $2,400 = 12 x $200 per month (not including initial membership fee)

- Tournaments - $4800 = 12 x $400 (1 tournament per month, a majority of them within driving distance). Cost includes gas and food (maybe sports drinks and energy bars). But is also a rough estimate of paying a pro to go watch the child play (Lil' Mo?) as well as overnight lodging at some events.

Total - $13,120

2013 - Age 9

Not much change happens between 8-10 years of age. The only difference will be accounting for inflation at a historical rate of approximately 3 percent.

Total - $13,513 = 1.03 x $13,120

2014 - Age 10

Total - $13,907 = 1.06 x $13,513

2015 - Age 11

The dynamics start to change on the part of the parent and child. Due to the initial investment made on the child, the parents and the player get more emotionally attached to the results. At this point, an “arm’s race” may begin to take place among the child’s immediate competitors. Therefore, they decide to “up the ante” a little bit and add more tennis, all in hopes of getting ahead of the competition (there’s always someone who’s better). The child is ranked in the top 300 on TR.net in the 6th grade and the he gets a taste of celebrity when he ventures out to a far-away national event. More and more discussions start to take place between players, parents and coaches with an emphasis on the national stage ("will he make it?" "does he have what it takes? Tell us, coach!"). The child wants to succeed at a higher level and the parents and still fully committed to supporting the child’s dream. After all, playing tennis is better than being a latch-key kid and the parents are so proud of the attention that the child is getting from other adults/parents. Can't let them down, can we?! The decision is certianly also influenced by the results of some of the kid's peers.

- Equipment - $800 (goot fill up that 6-pack bag with 6 brand new rackets. Chances are that he didn't like the rackets after all, so he has to switch twice in one year).

- Group Lessons - $3,840 = 12 x $320 (4hrs x week @ $20 per group)

- Private Lesson - $5,280 = 12 x $440 (2 privates per week x $55)

- Membership Fees - $4,800 = 12 x $400 (adding another club for extra court time, coaches, and variety of players)

- Tournaments - $7,500 = 15 x $500 (some tournaments require farther stays and duration)

Total - $24,219 = 1.09 x $22,220

2016 - Age 12

The only difference between 11 and 12 is the increase in duration per tournament (i.e., player stays in the draw longer; therefore, more cost to the parent), which accounts for a greater cost per tournament at $700. All other expenses remain relatively similar and there is no system for cost recovery in the mateur divisions.

Tournaments - $10,500 = 15 x $700

Total - $28,246 = 1.12 x $25,220

2017 - Age 14

The child lands an equipment preferred player program deal for being top 10 in his Section, but it doesn’t offset all the equipment costs because he is breaking more strings (more expensive strings) due to addtional on-court time and a stronger physique, running through more shoes, cracking more racquets (from throwing the racquet), new Tourna Grip for every match, and the Nike clothes to fit the part. To save money in the long-term, the parents purchase a $1,000 stringing machine to string racquets for the kid.

Group lessons are reduced to 3 times per week to allow for more outside match-play with adults and juniors. However, the group lesson prices go up because he is in a more advanced group with more personal attention (coach's hourly rate is split among 2-3 players rather than 4-5 or even 6). The parents decide to hire a trainer twice a week to increase the agility and quickness of the child. Why? Because everyone else is doing it! Also, the player may be too young to know what he needs to work on from a cross-training point of view. Additional costs may include match analysis and stroke analysis software (certainly not for every match and practice but, perhaps, once per year) as well as slo-motion videography.

Private lessons are bumped up to 3 times per week (so that the player can focus on specifics), mixing in a new professional who coaches all the best juniors around in hopes of getting more time with the pro in the future. The drive is three times as far for the third private lesson and slightly more expensive for the specialized expertise (supply and demand). Membership fees are static because the child is asked to play elsewhere as a guest, one of the benefits of increasing the level of play. More people want to hit with a better player. Tournaments are increased to 18 per year (the designated/manadatory for sectional rankings; national/super-national events; doubles; etc.) and a third of the tournaments require a flight or a severe cross-country drive.

- Equipment - $2,000

- Group Lessons - $3,600 = 12 x $300 (3 x per week @ $25 per group)

- Private Lessons - $8,160 = 12 x $680 (2 x per week @$55, 1 x per week @ $60)

- Membership Fees - $4,800

- Tournaments - $14,400 = 18 x $800

Total - $37,904 = 1.15 x $32,960

2018 - Age 14

The child struggles somewhat in his first year 14’s and the parents decide that lack of training is the problem. Despite living in Los Angeles, they seek out new options to maximize his tennis. First, they explore the big academies like Everts, IMG Academies, Saddlebrook, Newks, and Weil. The price tag is hefty, but the word is they develop Grand Slam Champions.

At the same time, the parents check out smaller outfits such as Gorins, Moros, Harold Solomon/Andy Brandi- just to name a few. The parents decide on Weil because it is close-by and their son can get the best quality training within a 2-300 mile radius.

According to Weil Tennis Academy, here is the Customized Boarding and Training Program:

Full Academic Year (August - June) - Customized Boarding & Training Program

- $43,000 US (including all application and insurance fees) [2011 figures – costs may increase or decrease in by 2018; note, also, that several other year-around academies come with an annual price-tag that is considerably higher - up to $68,000 or more]

- All the features of the Full time Standard Program plus

- 1 private tennis lesson and 1 semi-private tennis lesson per week

- 1 private fitness training time per week with a Certified Personal Trainer

- 1 month of private Mental Fitness Coaching

- 2 private Nutritional Consultations per semester

- One Year Individual Developmental Training Plan

- College Tennis Placement Program with Academy Director.

A couple things to point out, the child is getting a mix of individual, semi-private and group coaching and attention; he is receiving a regimented training schedule with a group of competitive kids in addition to the mental coaching and nutritional advice. The environment is energized and the player is racking up on-court hours towards that 10,000 hour goal. The caveat is that the $43,000 will only buy training from August to June. In comparison, the parents spent $38,209 in the previous calendar year.

Other costs associated with the academy are not factored into the base price such as more private lessons (Private Tennis Lessons with Weil Academy Head Coach: $110.00 per hour), transportation, coaching fees at tournaments, and most importantly, school. The parents want the child to succeed in academics, so they purchase the University of Miami On-Line Education for approx. $11,000 per year.

The tournament costs will increase significantly because the private coach is going to travel to San Antonio Nationals, Clay Courts, Sectionals, Eddie Herr Qualifying, and Orange Bowl Qualifying. Not to mention, family members want to tag along to the fun locations exotic locations like Miami and stay at the Biltmore Hotel (for purposes of this article, we’ll assume that this is not the only vacation for the family unit thus, the costs, are tennis-related).

- Equipment - $1,200

- Weil Tennis Academy - $48,000 = $43,000 + 5,000 (figure accounts for privates, transportation, coaching at tournaments)

- Education - $10,750

- Summer Group Lessons - $900 = 3 months x $300 (3 x week @ $25 per group, must prepay for Summer Session)

- Summer Private Lessons $2,160 = 3 months x $720 (3 x week @$60, old coach is out of the picture) Membership Fees - $4,800

- Tournaments - $19,800 = 18 x $1,100 (very conservative number)

Total - $103,379 = 1.18 x $87,610

2019 - Age 15

The Weil Academy did a great job in controlling all the things they can control, but the child was not ready to make this type of commitment so soon. He missed his childhood experience and became a bit deflated by the physical and emotional demands without the usual support group. Moving forward, the parents decide to bring the child home to LA and take time off, getting ready for the next big push: setting himself up for a top D1 collegiate scholarship.

- Equipment - $1,400 (switched from Wilson NXT to Big Banger)

- Group Lessons - $3,000 = 10 months x $300 (3 x week @ $25 per group, no tennis for 2 months after academy)

- Private Lessons - $4,800 = 10 months x $480 (2 x week @ $60, reducing the amount of private lessons)

- Membership Fees - $4,800

- Tournaments - 21,600 = 18 x $1,200

Total - $43,076 = 1.21 x $35,600

2020 - Age 16

Less is more. The child starts to piece things together with the technique, point construction, mind, and overall body coordination. He cracks the top 150 in his first year 16’s and things look promising for his second year 16’s. The parents start boasting about the upside potential of the aggressive game-style the child has developed- it was only a matter of time. Seeing the light at the end of the tunnel, the parents decide it is time to make a run for the top 50 USTA.

Staying the course of the previous year with the solid support staff, the parents decide to add a full-time personal trainer.

- Equipment - $1,400

- Group Lessons - $3,600 = 12 months x $300 (3 x week @ $25 per group)

- Private Lessons - $5,760 = 12 months x $480 (2 x week @ $60)

- Membership Fees - $4,800

- Off-Court Training - $7,200 = 12 months x $600 (3 x week @ $50)

- Tournaments - 21,600 = 18 x $1,200

Total - $55,006 = 1.24 x $44,360

2021 - Age 17

What a year 2015 was, a breakthrough year. He cracked the top 50 in the nation and is starting to make some noise with a few wins in the top 30 coupled with a few disastrous losses outside the top 100. The parents feel he is so close and he only needs a few more ounces of consistency to get him to the next level.

After speaking with various sources which included parents, coaches, ex-players, and the USTA- the parents settle on integrating ITF Junior Events into his schedule. The reasoning behind the decision is for stiffer competition and to attain a top 200 ITF ranking to impress the collegiate coaches. The “real” reason is everyone else is doing it, seems like the logical thing to do.

With that being said, someone needs to travel with the player, preferably a coach. A few families around the country decide on a knowledgeable coach to take the children to 10 (10 weeks of private coaching) different ITF events throughout the year. A majority of the tournaments are located within the United States with a few dipping into Central and South America.

- Equipment - $1,200 (costs are offset by a full racquet sponsorship with limited string)

- Group Lessons - $3,000 = 10 months x $300 (3 x week @ $25 per group, 2 months at ITF events)

- Private Lessons - $4,800 = 10 months x $480 (2 x week @ $60, 2 months at ITF events)

- ITF Coaching - $4,000 = 10 weeks x $400 per week (Coaching rate = $1,200 per week, 3 players traveling)

- Off-Court Training - $6,000 = 10 months x $600 (3 x week @ $50)

- Membership Fees - $4,800

- Tournaments - $32,000 = 20 x $1,600 (paying for coaches flight, parents at a few events)

Total - $70,866 = 1.27 x $55,800

2022 - Age 18

The moment of truth arrives. The child cracked the top 75 as a first year 18’s and is ranked in the top 300 ITF. A great year nonetheless and sets him up for a run at cracking the top 20 USTA and top 150 ITF. Who knows, maybe the child can participate in a Junior Grand Slam Qualifying Draw.

Colleges are littering the mailbox with letters, especially with the game-style the child demonstrates. Professional tennis is a long-shot, but the parents want to keep the door open for a career after college.

Marching on, the parents decide to keep the same schedule and sign early with a top school. They feel they have found the optimum training formula for their child.

- Equipment - $1,200 (costs are offset by a full racquet sponsorship with limited string)

- Group Lessons - $3,000 = 10 months x $300 (3 x week @ $25 per group, 2 months at ITF events)

- Private Lessons - $4,800 = 10 months x $480 (2 x week @ $60, 2 months at ITF events)

- ITF Coaching - $4,000 = 10 weeks x $400 per week (Coaching rate = $1,200 per week, 3 players traveling)

- Off-Court Training - $6,000 = 10 months x $600 (3 x week @ $50, 2 months at ITF events)

- Membership Fees - $4,800

- Tournaments - $32,000 = 20 x $1,600 (paying for coaches flight, parents at a few events)

Total - $72,540 = 1.30 x $55,800

End of Junior Career - AGE 19

The parents are satisfied with the journey with their child finishing in the top 20 USTA and top 150 ITF. The child settles at PRIVATE University on a 35 percent scholarship, with no guarantee of playing in the top 6 for his first year. Regardless, the child is going to earn a world-class education in return for competing for a top-tier program.

The Journey Is Not Complete

The road is just beginning for the child and his tennis journey to achieving his full-potential. Private University is an expensive university ($46,000) with little chance of pouring a full-scholarship his way in the future. During the summers, Coach Awesome recommends further training coupled with competing in a handful of ITF Futures events. After college tennis, the road to professionalism is tough. Everyone comes so far to only give up a few inches from the finish line. The last two hurdles in a 100 meter sprint are the toughest to conquer and require a significant amount of financial backing.

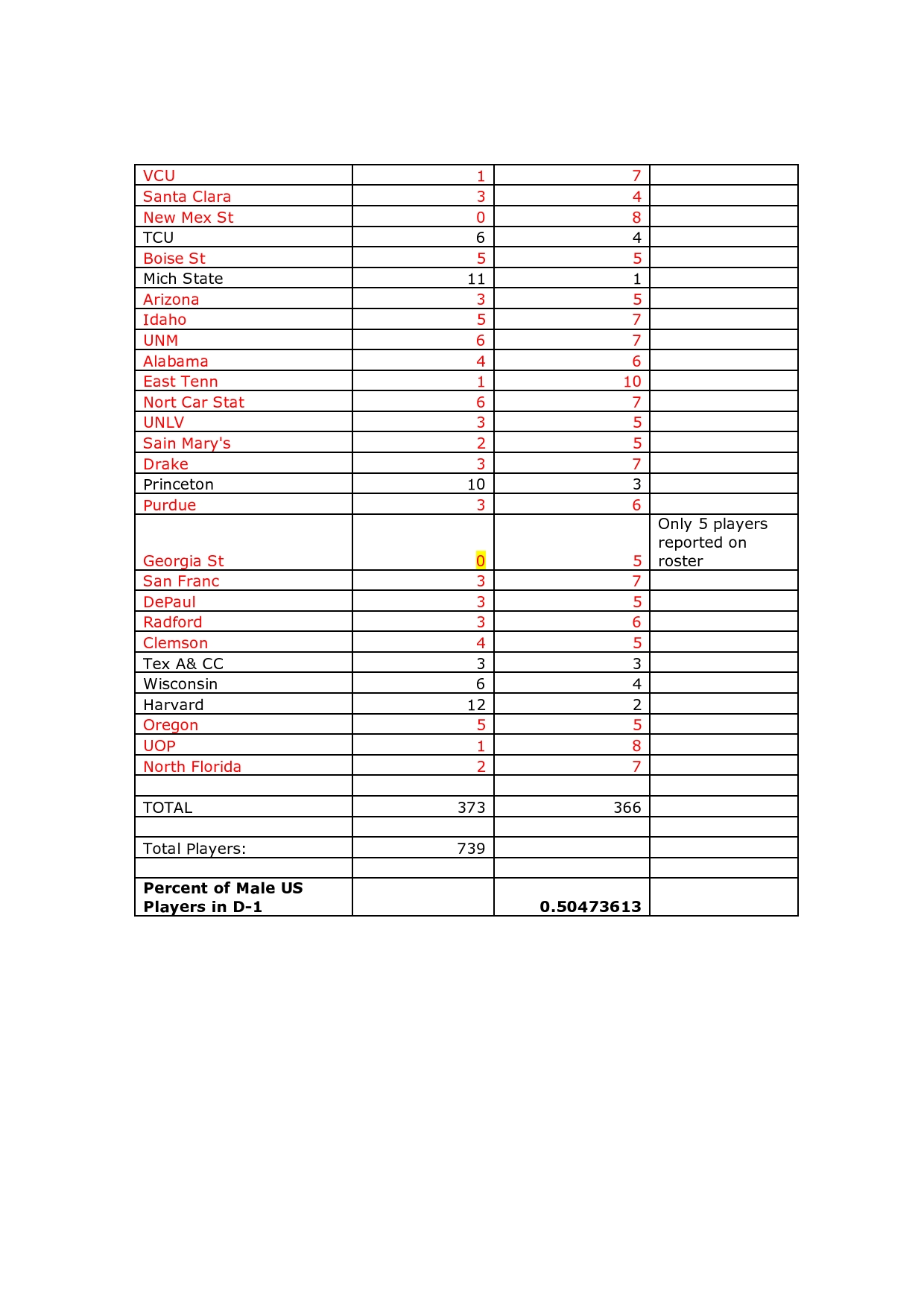

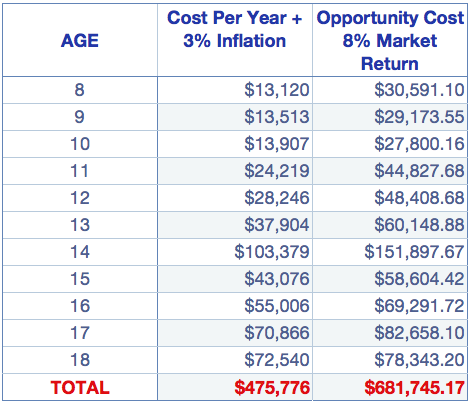

If we add up all the years, here is the total amount spent before setting foot on college campus:

= 13,120 + 13,513 + 13,907 + 24,219 + 28,246 + 37,904 + 103,379 + 43,076 + 55,006 + 70,866 + 72,540

= $475,776 is the GRAND TOTAL accounting for inflation from the age of 8-18.

What if families invested the money instead?

With an 8% annual market return over the same time period, the parents will have saved the following amount by today:

= 13,120(1.08^11) + 13,513(1.08^10) + 13,907(1.08^9) + 24,219(1.08^8) + 28,246(1.08^7) + 37,904(1.08^6) + 103,379(1.08^5) + 43,076(1.08^4) + 55,006(1.08^3) + 70,866(1.08^2) + 72,540(1.08)

= $681,745 is the opportunity cost.

Do you think that the $681,740 figure is high? Here are some thoughts (unfortunately, there's a glaring lack of outside information available):

- In talking about the state of college scholarships, David Benjamin, ITA Executive Director, says the following: “If parents invest $50,000 a year into their child's tennis career, some feel they're owed”. He goes on to say: "But it's not in the Constitution that if you spend a certain amount, you'll get a scholarship to the school of your choice. Intellectually, a family understands this, but emotionally it's difficult to accept. That's where you get the anger."

- According to the USTA’s “Going to College or Turning Pro? Making an Informed Decision!” (October 2010) prepared by Timothy Russell, Ph.D., the annual developmental value received at college is around $48,000/year (see Appendix A). That is, if it costs that university $48,000/year to train you, it is foreseeable that a player may spend about the same amount per year before entering college.

- "The expense of developing a world-class player from age 10 to 20 is astronomical — training, traveling, equipment," Martin Blackman (heads talent identification and development for the U.S.T.A.)

- Roger Draper, head of the British Lawn Tennis Association has estimated that the cost of developing a world-class player (Wimbledon champion caliber) is £250,000 (approx. $420,000). This, of course, taking into account fewer tournaments and less travel (given the smaller distances) in UK than in USA.

Here are some questions:

A. Do you think that the figures above are too high for the average family pushing for the top echelons of tennis? Are the figures just right? If you are a parent (particularly one who is NOT a tennis pro), please feel free to share your experience so far. Are there aspects that you have sacrificed in order to reduce the overall costs? Has your child obtained a college scholarship the value of which outweighs the monetary expenditure? What would you do different? What advice would you have for similarly situated families just starting out with the sport?

B. Even if the figures are not entirely spot-on (given that every family is different and some of the costs may be shared among siblings thereby reducing the overall average), one cannot deny that a great deal of money is, in fact, expected to be "invested" in a child's development and that the money would actually pay real-world dividends if used somewhere else (e.g. income producing property). If so, is there a way to get the same results (if not better) for a fraction of the cost? For, let's say, $50,000 - $100,000?

C. What steps need to be taken by the family, coach, club, regional organization, USTA, tournament organizers, academies, colleges, etc. in order to reduce the cost of developing across the board? Is there a road-map (CAtennis.com uses that term a lot) that each segment can follow in order to get the most out of tennis with least financial sacrifice? Why isn't anybody talking about this? What do the people "in the know" have to hide?

Sunday, December 11, 2011 at 12:21PM

Sunday, December 11, 2011 at 12:21PM  CAtennis

CAtennis  According to Patrick McEnroe: "We in the USTA maybe made a little mistake in pushing some of our junior prospects to go straight to the pros in the past. I think we lost a group who, if they had gone to college and had a chance to mature in every category, would still have had a chance to be a high-level professional....Only a small percentage of people playing college tennis will go pro, but if we can get a few into the top 100 we will be pleased... It can only increase our chances of producing a grand slam winner."

According to Patrick McEnroe: "We in the USTA maybe made a little mistake in pushing some of our junior prospects to go straight to the pros in the past. I think we lost a group who, if they had gone to college and had a chance to mature in every category, would still have had a chance to be a high-level professional....Only a small percentage of people playing college tennis will go pro, but if we can get a few into the top 100 we will be pleased... It can only increase our chances of producing a grand slam winner."