Steal This Drill: The Rainbow Drill

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 12:03PM

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 12:03PM  CAtennis

CAtennis  It is said that great minds think alike. As evidenced by the following drill, the same thing can be said about lesser minds as well (just kidding). The following drill is a collaboration between CAtennis.com, Karl Rosenstock and Roy Coopersmith. As it happened, and out of pure coincidence, the three parties discussed covering the following drill on exactly the same date.

It is said that great minds think alike. As evidenced by the following drill, the same thing can be said about lesser minds as well (just kidding). The following drill is a collaboration between CAtennis.com, Karl Rosenstock and Roy Coopersmith. As it happened, and out of pure coincidence, the three parties discussed covering the following drill on exactly the same date.

Here's a little background on our co-conspirators:

Karl Rosenstock: Karl is currently the official tennis X-mo cam videographer for USC Tennis and a Contributing Editor for CAtennis.com where he provides video content and articles. These days, Karl is most well known as the tennis slow mo guy insofar as he provides X-Mo cam high speed videography for tennis coaching and keepsake purposes for college tennis, tennis clubs and tennis tournaments. Karl has been a USPTA tennis teaching professional and professional television producer. He has specialties in producing, multi camera studio production and directing, lighting design and studio and remote camera operation. For more information regarding his services, please contact Karl at 415-794-5250.

Roy Coopersmith: Roy is currently the Tennis Director at Pine Bluff Country Club in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. With a tennis career spanning over 4 decades, Roy has done it all and seen it all. He was an accomplished professional, college, open as well as senior player (#6 in Germany in U40s) and, as a coach, he has had the opportunity to coach an impressive list of players including: Philipp Kohlschreiber, Lisa Raymond, Tom Shimada, Jelena Jankovic, Jamea Jackson, Christian Weiss, Toma Walter, Maja Palaversic, Christina Singer, Kim Couts, Roko Karanusic, Helena Vildova, Nguyen Hoang (2009 Orange Bowl Champion), Josip Mesin, etc. Currently, however, his main focus is on developing the game of his daughter - Niki Coopersmith. Nevertheless, if going to the next level is your goal, Roy has the technical, tactical, mental and physical expertise to assist you.

Rainbow Drill:

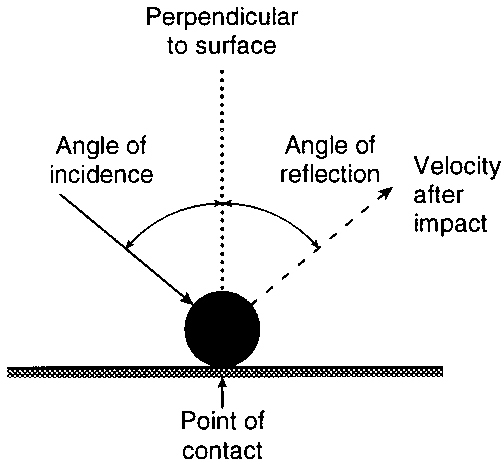

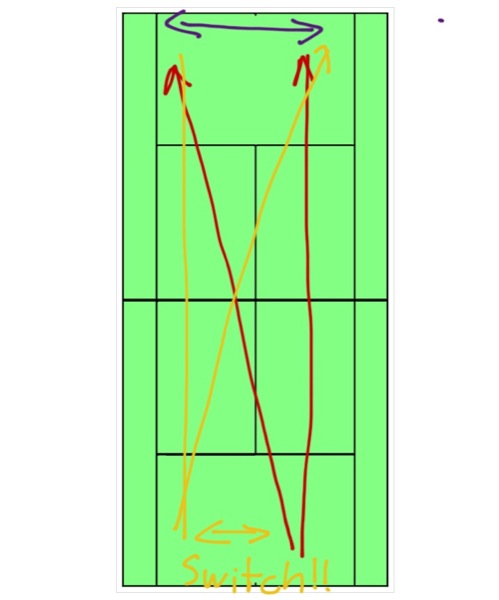

Here, at CAtennis.com, we are huge fans of situational-based practice. We feel that if the players have experienced certain pressure situations in practice they will be able to relax and think more clearly in the heat of battle. In the Rainbow Drill, one of the players starts with his racket on the net chord and the other is on the baseline. The coach (or the baseline player) feeds a deep lob over the net-player. The lob should bounce somewhere close to the baseline (even slightly outside of the lines). The net player chases it down and either hits a baseline overhead or a groundstroke. The baseline player must let this ball bounce and the point starts immediately (i.e., if the net player misses the "feed" he loses the point). This drill is not only a fun variation on the ol' baseline game, but it also teaches the players how to hit overheads from less than optimal positions and, also, how to regain the advantage after having lost it. This is particularly important for juniors and female players bacause they may lack the put-away ability from the net. That is, sometimes players get to the net but fail to capitalize on the situation and are forced to "restart" the point if the opponent comes up with a decent lob. This drill will, hopefully, teach the players that losing the upper hand mid-point is not the end of the world. One can regain the advantage with a well placed shot...a shot that must be practiced and mastered.